The Talk: How to Convince Elderly Parents to Move

March 17, 2020

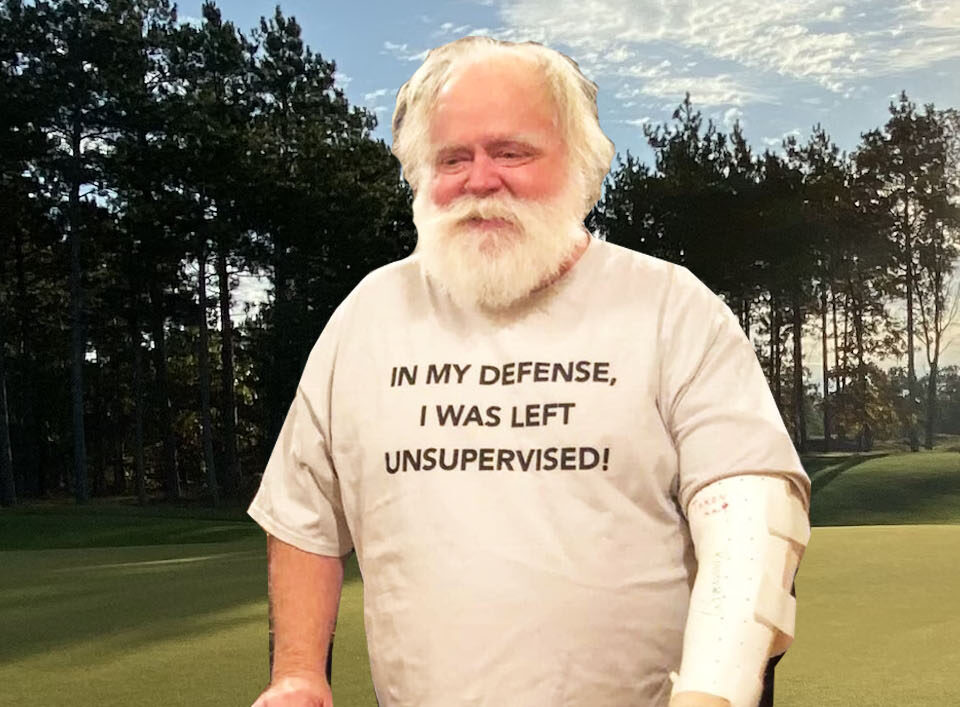

Bill Schnell

Our family has always had a rather strange relationship with death. As relatively new parents with young children at home, an occasional treat was visiting a random cemetery to stroll among the headstones. While still in our thirties, my wife, Nancy, and I bought our grave plots. In our early forties, we had rather quirky granite monuments engraved and placed upon those plots. Nobody we know has done that at such a young age.

I do not believe that our family’s approach to death is so strange as our present culture’s denial of the same. That denial is reflected in the vast resources our culture commits to cosmetic products, appliances and surgeries which are always intended to make us look younger and further removed from the great inevitable. It is also reflected in our attitudes toward the aged which, in many ways, relegates the latter to the margins of society and beyond our range of daily sight.

Wisdom of the Elders

It is not that way in other cultures. Atul Gawande, author of Being Mortal, recalls his aged grandfather in India:

…he was revered—not in spite of his age but because of it. He was consulted on all important matters—marriages, land disputes, business decisions—and occupied a place of high honor in the family. When we ate, we served him first. When young people came into his home, they bowed and touched his feet in supplication (Gawande, 2017, p. 14).

Whatever happened in our culture to distance us from aging and death happened relatively recently. Gawande also notes: “Whereas today people often understate their age to census takers, studies of past censuses have revealed that they used to overstate it. The dignity of old age was something to which everyone aspired” (Gawande, 2017, p. 18).

Old age, as we measure it, was certainly rarer then. At birth in 1900, North Americans had a life expectancy of 48 years while Latin Americans only had a life expectancy of 29 years (PAHO, 2012). Before the advent of modern medical treatments and technology, a broken hip was typically regarded as the beginning of the end. A broken hip would land a person in bed on the first floor at home where lungs would soon become compromised from lack of deep inflation and pneumonia would set in. “Sir William Osler, sometimes called the father of modern medicine, famously called it ‘friend of the aged’ (often rendered as ‘the old man’s friend’) because it was seen as a swift, relatively painless way to die” (President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2007, p. 6).

The Medical Community’s Over Optimism

Certainly, “a swift, relatively painless way to die” is preferable over a protracted and painful death. Unfortunately, the same modern medical and technological advances which enable us to live longer can also condemn us to die longer–and more painfully–if not administered with a measure of wisdom. Wisdom, according the Hebrew scriptures, can be found in looking squarely at death instead of averting our gaze in denial. The scripture engraved upon my grave monument reads: “Teach us to number our days aright, that we may gain a heart of wisdom” (The Thompson chain-reference Bible, 1983, Psalm 90:12).

It is not normative to number our days aright while surrounded by a culture in denial of death. We would prefer to number our days “awrong” and believe that we will live forever. One unfortunate consequence of perceiving an unlimited supply of anything is our tendency to waste it. We sprinkle fresh water upon our lawns until a severe enough shortage causes us to count every drop. The wisdom we gain from counting our days aright teaches us that each day is much too precious to squander with needless pain, suffering and anxiety. But, again, we are steeped in a culture that is in denial of death and where people avoid counting their days.

It is also the culture in which our medical professionals are trained, and the result is a measure of wisdom lacking among them despite their being among the best and brightest. Together with modern technology, medical professionals are very good in diagnosing our medical issues. They should be as good about rendering a prognosis (how a particular diagnosis plays out the preponderance of the time) but they are demonstrably not when it comes to end of life issues. One study of five outpatient hospice programs in Chicago, including 365 doctors and 504 patients, “found that only 20% of prognoses were accurate. Most predictions (63%) were overestimates, and doctors overall overestimated survival by a factor of about five.” Moreover, these predictions were “objectively communicated to the investigators and not to patients themselves” (Christakis, 2000).

We might ask why doctors are reluctant to offer specific prognoses to patients and why they tend to overestimate survival rates and timing. Some researchers have found that “…physicians generally feared disclosing a diagnosis of cancer because they wanted to protect patients from interpreting the diagnosis as meaning certain – and probably, believed to be painful – death” (Gordon, E. J., & Daugherty, C. K., 2003). Doctors have, after all, gone into the healing arts with the hope of healing. They are steeped in a culture that fears death. Few of us, doctors included, are emotionally equipped to tell others that they are dying. It feels as if we are robbing them of their last shred of hope.

“American physicians fear that the revelation of a grim prognosis may psychologically damage patients’ hopes and metaphysically diminish their will to survive….” (Gordon, et al., 2003). As one physician put it: “…you’re doing exactly the opposite of why they’re coming to you. They’re coming here primarily for the hope. And so, to slam bad news in their face is counterproductive to why they’re coming….” (Gordon, et al., 2003).

And it is not only hope in patients that doctors want to preserve.

Doctors want to preserve hope in their patients—and probably also in themselves (one becomes a doctor to save lives, after all). ‘Talking about end of life is difficult for many physicians and their patients and has been a taboo topic in society generally,’ the APA writes. Doctors struggle to tell patients a cure is impossible; they’re often uncomfortable discussing treatment decisions, like whether the hospital or the home is the best setting for the patient. And some physicians believe they must do everything possible to prolong life no matter how much pain is involved. Some fear that offering palliative care and pain management suggests they’ve quit trying to help their patients, or that they’ve failed in their duties, the APA says. What’s more, few doctors receive education on these absolutely crucial conversations. (Lopatto, E., 2015, para 10).

Ignorance is not Bliss

As a result of these attitudes, fears and lack of training, doctors are either overoptimistic in their prognoses or reluctant to share any prognosis with the patient in a terminal condition. But ignorance is definitely not bliss in this circumstance. Regardless of the cultural milieu in which doctors live and receive their training, and in spite of all good intentions to keep hope alive, withholding prognoses or offering over-optimistic projections simply leads to poor medical decision-making at the end of life. First, “…doctors may contribute to patients making choices that are counterproductive. Indeed, one study found that terminally ill cancer patients who hold unduly optimistic assessments of their survival prospects often request futile, aggressive care rather than perhaps more beneficial palliative care” (Christakis, 2000).

There are two complementary points being made here. The first is that unrealistic hopes and prognoses encourage patients to seek aggressive treatments which they would not seek with more accurate information (and that even doctors would not seek knowing what they know and fail to report).

Studies from the United States, England, Canada, Japan, Norway, and Italy consistently show that patients with cancer generally were willing to undergo aggressive treatment with major adverse effects for very small chance of benefit, different from what their well physicians or nurses would choose. (Harrington et al., 2008).

Indeed, “…there would be far less aggressive treatment at the end of life if patients were honestly informed of the ‘shear futility’ of such experimental intervention” (Gordon, et al., 2003).

Hospice, a Gentler Way Home

A second complementary point is that ill-informed patients do not, in a timely fashion, avail themselves of palliative care designed to alleviate the needless suffering of aggressive, long-shot therapies and, similarly, do not avail themselves of hospice care. Palliative care aims to control pain and discomfort rather than to cure. An example is provision for a

COMFORT PACK: It contains a dose of morphine for breakthrough pain or shortness of breath, Ativan for anxiety attacks, Compazine for nausea, Haldol for delirium, Tylenol for fever, atropine for drying up the wet upper-airway rattle that people can get in their final hours (Gawande, 2017, p. 162).

Hospice care offers palliative care specialists trained in the use of comfort packs; and residential or in-home caregivers trained in family support, listening skills and other compassionate responses for those who are terminally ill.

Unfortunately, “…undue optimism about survival prospects may contribute to late referral for hospice care, with negative implications for patients. Indeed, although doctors state that patients should ideally receive hospice care for three months before death, patients typically receive only one month of such care” (Christakis, 2000). Sometimes it is much less than one month, and this trend has been increasing. “The median length of stay on hospice has declined from 29 days in 1995 to 26 days in 2005, with one-third enrolling in the last week of life and 10% on the last day of life” (Harrington, 2008). The results of one study are telling: “…those who saw a palliative care specialist stopped chemotherapy sooner, entered hospice far earlier, experienced less suffering at the end of their lives—and lived 25 percent longer” (Gawande, 2017).

Further, to the extent that palliative care and hospice ease the stresses and strains of family caregivers, there is evidence to suggest such interventions promote longer and better lives remaining to those caregivers. According to one study,

…participants who were providing care and experiencing caregiver strain had mortality risks that were 63% higher than non-caregiving controls (relative risk [RR], 1.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.00-2.65). Participants who were providing care but not experiencing strain (RR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.61-1.90) and those with a disabled spouse who were not providing care (RR, 1.37; 95% CI, 0.73-2.58) did not have elevated adjusted mortality rates relative to the non-caregiving controls.

Conclusions: Our study suggests that being a caregiver who is experiencing mental or emotional strain is an independent risk factor for mortality among elderly spousal caregivers. Caregivers who report strain associated with caregiving are more likely to die than non-caregiving controls.

Beyond that, “…strained caregivers compared with age- and sex-matched non-caregiving controls have significantly higher levels of depressive symptoms, higher levels of anxiety, and lower levels of perceived health” (Schulz, R., & Beach, S. R., 1999).

The Societal Cost of Over Optimism

Finally, to the extent palliative care and hospice options are vastly less expensive than long-shot treatments with little chance of success, the former may be good for the nation.

The soaring cost of health care has become the greatest threat to the long-term solvency of most advanced nations, and the incurable account for a lot of it. In the United States, 25 percent of all Medicare spending is for the 5 percent of patients who are in their final year of life, and most of that money goes for care in their last couple of months that is of little apparent benefit. (Gawande, 2017).

The conclusion of the research cited here is that doctors are ill-equipped by their training and cultural conditioning to offer realistic prognoses to those at the end of life. They are much more inclined to offer over-optimistic projections which negatively impact medical decision-making for those with terminal conditions. Patients are more inclined to choose aggressive treatment options with adverse side-effects and little chance of success, all at the expense of more beneficial palliative and hospice care choices. These poor medical decisions may actually serve to reduce the quantity of life, but certainly the quality of life. And even where they add time, it is in effect causing patients to die longer rather than live longer—all to the harm of the dying, their caregivers and the culture-at-large. But knowledge is power, and what follows will be a strategy to maximize the chances of dying well when the time comes.

How to Work with Doctors

We have seen that medical professionals are products of cultural conditioning just like the rest of us. Doctors in particular are intelligent, having successfully navigated the endurance contest that is medical school. They have chosen a noble profession and they have noble intentions. But their training, while outstanding in certain areas of professional competency, has been lacking in the areas of philosophy and ethics. You can help them help you. First, think like them. Then get them to think like you.

You can begin by recognizing that they are exceedingly busy. Make the most of their time when they stop by a hospital room by having written out your questions ahead of time. Whenever you think of a question, write it down so that it won’t be forgotten in the brief time you have with a doctor. These doctors have become guarded as a protective mechanism. They have been threatened with malpractice suits, verbally assaulted and or rare occasions maybe even physically assaulted for simply telling the truth about a loved one’s condition. Understand that not everyone accepts the truth well. Physicians don’t always know you and how well you accept the truth, so you will need to help them understand you.

Tell them you appreciate their good work. Explain that you are a knowledge-is-power kind of person and that not knowing is the worst for a person like you.

Even then you may suspect some equivocation on their part. Press them on this. They live, breath, eat, sleep their practice of medicine. They know with a fair amount of certainty how most situations play out over a predictable time frame. You need to know certain fundamental things in order to make informed medical decisions. If a diagnosis is terminal, you need to know that. You need a realistic prognosis to determine whether treatments (and possible adverse side effects) are worth it in terms of quantity and quality of life. You need to know the odds.

Hopefully, doctors will come to trust that you can, indeed, handle the truth and they will share their best assessments. Then thank them again.

Allowing Elders to Choose for Themselves

Assuming that the prospects for the patient you are advocating for are grim, err on the side of palliative and hospice care if the timeframe of the prognosis allows for this (6 months or less in Ohio). Understand that “One of the largest barriers to hospice in the United States is the way it is defined in the Medicare Hospice Benefit. Patients must have a life expectancy of 6 months or less and must forego curative treatment” (Harrington, et al., 2018). In other words, Medicare will cover either curative treatment or hospice care, but not both. Once we go into hospice, we are crossing a line that acknowledges a forfeiture of payments for curative treatments.

The question for me is: “What is the prospect of being restored to a meaningful life?” If the prospect is good, I am all for fighting the good fight. But if it is not good, my main concern is the avoidance of needless pain and suffering at life’s end. I might be willing to endure some discomfort to return home for a “libation” now and then. I might even stick around for a little while because somebody emotionally needs me. What I really want is a choice.

The choice is more important to me than the actual exercise of it. So, you will find that there is plenty of choice reflected in my Living Will. I can choose to not be intubated. I can choose to not receive artificial nutrition and hydration. I can choose highly addictive opioids. I may endure some pain before the choice is executed, but knowing I have a choice is comforting.

Fear of Death vs. Fear of Suffering

“…It may be true for some people that when they say they are afraid of death what they mean is that they are afraid of the process of dying….” (Kagan, 2012, p. 295). That certainly describes me.

I am rather like movie critic Richard Ebert in this respect, as described by one author. Ebert is dying in increments, and he is aware of it.

“I know it is coming, and I do not fear it, because I believe there is nothing on the other side of death to fear,” he writes in a journal entry titled Go Gently into That Good Night. “I hope to be spared as much pain as possible on the approach path” (Jones, C., 2018).

While I have a healthy survival mechanism, I can’t say that I have lived in dread of dying. Pain and suffering, on the other hand, are things I would prefer to avoid ifpossible. To the extent you can further physical and emotional comfort in the midst of distress, I will be eternally grateful. I’ll let you know how I’m feeling. If I can give you the “peace sign” to signal my return to awareness after surgery, maybe you can give me some respite to stretch my arms should they be otherwise tied to the bedrails for my protection.

Letting Go

My dad’s health declined rapidly after complications developed following heart surgery. In his final days he couldn’t speak due to a tracheotomy. I wondered if he felt helpless in communicating about needful things. Maybe it occurred to him that the lawn mower needed to be mothballed for the winter, or something like that.

Wanting to ease his mind I asked him, “Just tell me what you want, and I’ll see to it.” Then I watched carefully to read his lips. He mouthed, “I want mom to be happy.” That was a tall order under the circumstances, but I remembered it. A few years after he died one thing led to another and I introduced mom to an elderly gentleman from church. The two hit it off, went on several trips together and enjoyed each other’s company. Sometimes I’d wind the mantle clock, look at dad’s picture next to itand say, “Well, you said you wanted her to be happy.”

Mom liked a good night out. Sister Betsy and I would spring her from the assisted living joint and, at a local restaurant, sneak her a Manhattan (against doctor’s orders I presume). One time, as Betsy and I gabbed a mile-a-minute, to get a word in edgewise mom blurted out: “This was a great idea!” It made us so happy to see her happy, and to think that dad would be pleased.

On the night my dad passed I was attending the opera in Cleveland. During the performance I received a silent page from my sister with a predetermined code (911). I made my way to a phone and called her. Both sisters and my mother were at the hospital while dad’s heart was arresting. Doctors had revived him, only for him to arrest again. Cardiac resuscitation can be a violent process and elderly patients who survive it are often never the same again.

The doctors asked my mother what she wanted them to do if he arrested again. Mom just didn’t have it in her to say “stop,” and neither did my sisters. I was elected to make the determination. They handed the phone to the doctor and I asked him, “What would you do if this was your father?” He responded, “I’d let him go.” So, I told him, “Let him go.” Dad died a few minutes after that. I have never had cause to regret that decision. I do wish I could have been there with him. But more importantly I was there for him when he needed me most. It will please me to have someone there for me when the time comes.

A Bad Death is Not Inevitable

An author prefaced an article with these words: “Death is Inevitable. A Bad Death is Not.” (How to Have a Better Death, 2017). Aging and dying parents change the family dynamic. Children have different ideas about what is in their parents’ best interest. Siblings disagree, sometimes heatedly. If disagreement progresses to demonization, watch out because the eroding of trust bleeds over into financial matters.

Don’t beat yourself up if things don’t go exactly according to plan. Remember,

…all we can do is get on with trying to make sure we write the best chapters of our lives that we can, while contributing some good lines and passages to those of others. We can’t guarantee that the great editor of fate won’t ruin it by inserting an ugly ending. But we can give the bastard as little help as possible (Baggini, J., 2018).

I have only gratitude for having been made a wee part of the great grand scheme of things for this little while.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

About The Rev. Dr. William Schnell

The Rev. Dr. William F. Schnell (Bill) retired as Senior Pastor from The Church in Aurora (Aurora, Ohio) in 2018. In a ministry spanning 36 years and three congregations, and even now informed by his studies, he frequently explores issues of aging with dignity and grace, coping with tragedy and maintaining a healthy outlook. His continuing work finds him frequently visiting homes, hospitals and hospices where he serves, and learns from, the sick and dying.

A former President of the Ohio Council of Churches, a delegate to the National Council of Churches and participant in World Council of Churches events, Bill has been a pastor to pastors who labor with him in ministering to those in need.

He is currently the longest-serving board member of the Portage County Community Action Council, has received the Outstanding Service Award from Habitat for Humanity, and has been twice recognized by the International Council of Community Churches with the Charles A. Trentham Homiletics Prize.

Bill holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in Political Science from Capital University, a Master of Arts in Community Leadership from Central Michigan University and both the Master of Divinity and Doctor of Ministry degrees from the Methodist Theological School in Ohio. While in retirement, he has completed a Summer Theology School at Oxford University in England, is presently obtaining a Graduate Certificate in Social Justice at Harvard University, and plans to continue his studies at Yale focusing on Climate Change and Health.

This essay is excerpted from a paper he wrote at Harvard for a class entitled, “Dying Well.” It has a firm undergirding in current research which includes peer-reviewed studies and books by authoritative medical practitioners, educators and some who speak from the voice of experience about grief and loss. Bill’s emphasis is on palliative and hospice care as a needed balance for medical interventions that are often based upon over-optimistic prognoses from a well-intentioned but, in certain critical areas, ill-informed medical establishment.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

An Ohio based LLC founded in 2018, Operation Relo provides a comprehensive set of services for families with elders who may need to downsize, especially when the children are out of town. The company develops and executeselderhood plans addressingPOA, medical, financial, executorial, and lifestyle coaching issues; preparing homes for sale with repairs and staging; relocating possessions through estate sales, storage, donations and disposal; clearing and cleaning the house; and conducting senior moves. Contact us at (877) 678 – RELO (7356), [email protected] and www.operationrelo.com

___________________________________________________________________________________________

References

Angell, R. (2017, June 19). Over the Wall. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/11/19/over-the-wall

Baggini, J. (2018, November 24). Would philosophy help me to deal with my father’s death? – Julian Baggini | Aeon Essays. Retrieved from https://aeon.co/essays/would-philosophy-help-me-to-deal-with-my-father-s-death

Christakis, N. A. (2000). Extent and determinants of error in doctors prognoses in terminally ill patients: Prospective cohort study Commentary: Why do doctors overestimate? Commentary: Prognoses should be based on proved indices not intuition. Bmj,320(7233), 469-473. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7233.469

Gawande, A. (2017). Being mortal: Medicine and what matters in the end. New York: Picador, Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company.

Gordon, E. J., & Daugherty, C. K. (2003). Hitting you over the head: Oncologists disclosure of prognosis to advanced cancer patients. Bioethics,17(2), 142-168. doi:10.1111/1467-8519.00330

Harrington, S. E., & Smith, T. J. (2008). The Role of Chemotherapy at the End of Life. Jama,299(22), 2667. doi:10.1001/jama.299.22.2667

Jones, C. (2018, November 05). Roger Ebert: The Essential Man. Retrieved from https://www.esquire.com/news-politics/a6945/roger-ebert-0310/

Kagan, S. (2012). Death (The Open Yale Courses Series). Yale University Press.

Lopatto, E. (2015, February 23). Everything I know about a good death I learned from my cat. Retrieved from https://www.theverge.com/2015/2/23/8069825/everything-i-know-about-a-good-death-i-learned-from-my-cat

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), Latin America and the Caribbean Have Gained 45 years in Life Expectancy Since 1900. (2012, September 18). Retrieved from https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=7194:2012-latin-america-caribbean-have-gained-45-years-life-expectancy-since-1900&Itemid=1926&lang=en

President and Fellows of Harvard College. (2007, July). An Update on the “old man’s friend”. Harvard Health Letter, 6. www.health.harvard.edu

Schulz, R., & Beach, S. R. (1999). Caregiving as a Risk Factor for Mortality. Jama,282(23), 2215. doi:10.1001/jama.282.23.2215

The Thompson chain-reference Bible: Containing Thompsons Chain-references and text cyclopedia, to which has been added a new and complete system of Bible study … (1982). Indianapolis, IN, U.S.A.: B.B. Kirkbride Bible. Psalm 90:12

White, C. (2014). She Ain’t Perfect. On Making Noise [Album]. Unicoi County, Tennessee: Backwoods Music, LLC (2014)