The Senior Change

April 3, 2024

The Talk: A Convincing Discussion About Senior Moves

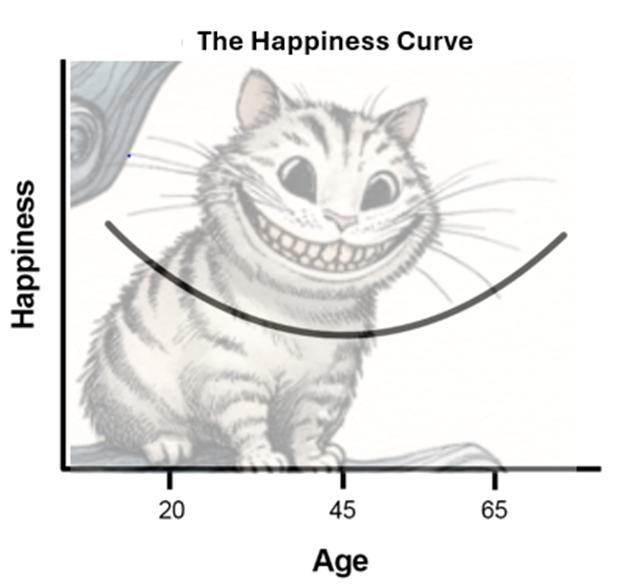

May 6, 2024Darn, another gray hair. Where are those keys? My aching joints! We’ve certainly heard about the torments of senior living, but did you know elders are the happiest people alive? The Happiness Curve shows it’s a true scientific fact, sort of.

The (Social) Science of Happiness

The relationship between chronological age and happiness has been reported in scores of published research papers1-68. Most use surveys that asked people between age 20 and 90 to report how happy they feel on a 1 to 10 scale. Relatively-speaking, twenty-year-olds report high levels of happiness, which steadily decline as people age, bottoming out somewhere in their 40s. Then the trend reverses and climbs ever higher. When plotted, a Cheshire smile emerges.

This confounded some sociologists – many of whom were likely in their 30s and 40s — who launched numerous studies to challenge that sardonic grin on a host of issues often focused on the very definition of happiness and data issues like the cohort effect, which notes that happiness scores may be distorted by external events. 69, 70, 71, 72, 73 Consider a 20-year-old who is otherwise happy but is facing conscription during a war. He is likely to report lower happiness scores than a 45 year old in mid-life crisis but still answering on VE Day after Hitler was defeated. When statisticians correct for such data ripples, the familiar happiness grin consistently returns.

Under the Covers

Importantly, the studies don’t conclude that the same things making a 20-year-old happy will also cheer an elder. For example, a twenty-something may experience a heightened thrill crawling into work and narrowly eluding dismissal after a night of ribald socializing with new friends, while an octogenarian may report similar levels of bliss reading a book from their favorite author after tucking in a granddaughter and retiring with the fourth movement of Beethoven’s Ninth. The youth may not yet appreciate Beethoven let alone imagine being a grandparent. The elder may fondly recall similar nocturnal exploits without desiring to repeat them.

Freedom brings youthful exuberance. Sprung forth from oppressive parental custody, the emancipated youth gambols out in search of adventure and pleasure. But indulgence brings consequences. You can’t eat or drink as much without getting puffy. That great job which afforded a new car and nice house also brought along a 30-year mortgage. Sex brings all kinds of complications.

By the time they reach 45, they know they’re not as happy as 25. Yet never having been 65 years old, they can’t imagine getting older will make it better. That runs counter to their entire life experience.

Another bracing consideration is that most lives will be touched with calamity of some kind – death of someone close, career devastation, something with a child, financial crisis, a divorce. It’s a numbers game, and by middle age, their tragedy number has probably been called at least once.

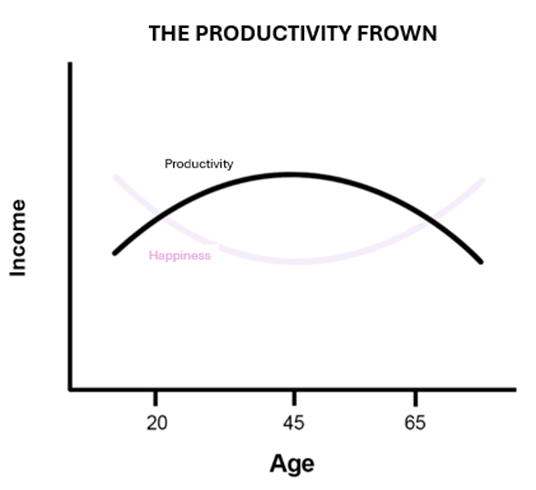

The Frown Curve

For many happiness isn’t even an articulated goal, in part because we live in civilizations that were formed to facilitate survival, and productivity is more important for survival than happiness. It follows then that our institutions – education, government, religion, employment – focus on making us more productive.

Using income as a proxy for productivity, we note that twenty-year-olds have little income. Often they are students doing part-time work until securing a toehold in the workforce with that all-important first job. Relieved, they pour effort into the job and are rewarded with higher levels of pay. These pay increases are mixed with a liberal doses of performance reviews, office politics, and business perquisites, culminating around the late 40s which are considered the prime earning years.

For most, the pace of career progress sputters, and income growth is reduced or reversed. An ever-smaller percentage of workers continue their ascent up the income pyramid, but the broad majority face stagnant or declining wealth as they are shoved out of the workforce to make way for the next generation. The effects of reduced job opportunities for older workers produces a Frown Curve, which is ironically the near-perfect inverse of the Happiness Smile.

The Best Oxymoron: a Happy Elder

To a beleaguered 48-year old, and upward ascent promised by the Happiness Smile may seem implausible. Their bodies ache like never before, they have crushing debt, and it’s just about college time for the kids. On top of that, the good-paying jobs they once enjoyed are now being reserved for people several decades younger.

Sorting out what comes next feels like piecing together a message from an Ouija board, letter by letter, but for many, good cheer does emerge.

Being old does have some advantages. By definition, older people have been here longer, resulting in many more experiences with many people in many different situations. Even if they’ve never picked up a book in their lives, older folks know how to deal with people better,74 and interacting with people requires a lot of energy.

Think about the engineer programming robots. They all report that everyday human tasks account for a huge amount of processing power. It’s the same for humans. Both are increasingly learning machines that continuously develop short-cuts. Some examples: To avoid debilitating, wasteful conflict, elders can navigate around that recalcitrant clerk, perhaps using honey instead of vinegar. They know how to get their taxes filed on time, even if they still grumble, and they are no longer slaves to fashion, or slaves to anything else really. They’ve learned what can be ignored and what requires attention.

They also are out of the rat race. For those who had defined their self-worth by their jobs, the exit was devastating. But after a few years and they’ve survived, elders can appreciate the high price the workplace had been extracting.

Older folks reflect this with a gentle, faraway look in their eyes. Some call it spiritual. Some say grandpa is out of it again, but that’s often how a quiet joy looks, emerging from years of struggle.

There was an older woman sitting in the sun outside an assisted living facility recently. A young worker struck up a conversation with her, eventually asking, “Is it depressing to be living here with so many people here dying all the time?” The old gal simply smiled at the youngster and said, “No honey. We’re all sitting here on heaven’s doorstep.”

Keep the Email Coming

Finally, recall the points along the Happiness Curve are a nexus of average scores. Just because most people get happier doesn’t mean everyone gets happier. There are choices that will improve the odds of having a happy senior life.

First, restructure and refresh. Make your surroundings compatible with your particular elder lifestyle, with what you want to do next. That big house was great for raising kids, but now most of those bedrooms are empty, the big lawn needs to be cut, and most of the stuff in your attic won’t ever be used again. Lighten your load. Throw out old clothes that don’t fit the times. Go buy yourself something nice, even if it’s just a trifle.

Also, don’t go it alone. Pay attention to your social life. Many choose to retire, but work per se isn’t a dirty word. When pursued with purpose it has many non-monetary benefits. If you just can’t stomach any more formal employment, participate in hobbies or volunteer for something worthy

Lastly, stay in the game, and share your thoughts, feelings, and learnings. With so many disorienting changes, getting old can make you feel isolated and maybe even hostile. Some say they’ve earned the right to be crabby after what they’ve been through, which is your prerogative. But remember, other people also have the prerogative to avoid cranky people. Reach out to them in a way they understand.

When my dad was in his 80s, his kids and grandkids were all off pursuing their own lives scattered around the world. We were family but didn’t really know each other that well. Some wise soul set up an email group for the family, and we started sharing posts, perhaps out of reflexive habit, perhaps out of obligation.

All was going along when one day Grandpa Kevin reintroduced himself as GPK. It was a small gesture, but the moniker was hip yet grounded, setting the tone for many future exchanges which were often more honest and vulnerable than we ever felt comfortable sharing in person. GPK doesn’t send emails anymore, but we still get his messages.

About Operation Relo

Operation Relo provides a comprehensive downsizing services for families with elders. Senior support services include preparing older homes for sale; moving & shipping; and redistributing household possessions through cyberselling, estate sales, storage, donations, and disposal. Whatever it takes. Find us at OperationRelo.com, (877) 678 – 7356 (RELO), and [email protected].

© Operation Relo, 2015 – 2025

Please tell us if you reprint or link to our content.

Footnotes

1 Blanchflower, David, Oswald, Is happiness U-shaped everywhere? Journal of Popular Economics, September 2020, Volume 34, 575-624

2 Argyle M (1999) Causes and correlates of happiness. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.) Wellbeing: the foundations of hedonic psychology New York: Russell Sage: 353–373.

3 Argyle M(2001) The psychology of happiness, 2nd edn. Routledge, New York

4 Baird B, Lucas RE, Donovan MB (2010) Life satisfaction across the life span: findings from two nationally representative panel studies. Soc Indic Res 99(2):183–203

5 Bell DNF, Blanchflower DG (2020) US and UK labour markets before and during the COVID-19 crash. Nat Inst Ec Rev 252:R52–R69

6 Blanchflower DG (2020a) Is happiness U-shaped everywhere? Age and subjective well-being in 132 countries. NBER Working Paper #26641, January.

7 Blanchflower DG (2020b) Unhappiness and age. J Econ Behav Organ 176:461–488

8 Blanchflower DG (2009) International evidence on well-being in Measuring the Subjective Well-Being of Nations: National Accounts of Time Use and Well-Being. In: Alan B (ed) Krueger, editor NBER and. University of Chicago Press, pp 155–226

9 Blanchflower DG, Graham C (2020a) The mid-life dip in well-being: economists (who find it) versus psychologists (who dont)! NBER working paper #W26888, March.

10 Blanchflower DG, Graham C (2020b) Subjective well-being around the world: trends and predictors across the life span: a response, working paper. http://www.dartmouth.edu/~blnchflr/papers/dgbcg%206%20March%20commentary.pdf

11 Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ (2019) Do modern humans suffer a psychological low in midlife? Two approaches (with and without controls) in seven data sets. In The Economics of Happiness. How the Easterlin Paradox Transformed Our Understanding of Well-Being and Progress, edited by Mariano Rojas, Springer.

12 Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ (2008a) Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Soc Sci Med 66:1733–1749

13 Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ (2004) Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. J Public Econ 88(7-8):1359–1386

14 Bookwalter, J, B. Fitch-Fleischmann B, Dalenberg D (2011) Understanding life-satisfaction changes in post-apartheid South Africa. MPRA Paper No. 34579.

15 Cantril H, (1965) The pattern of human concerns. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ.

16 Charles ST, Reynolds CA, Gatz M (2001) Age-related differences and change in positive and negative affect over 23 years. J Pers Soc Psychol 80:136–151

17 Cheng TC, Powdthavee N, Oswald AJ (2017) Longitudinal evidence for a midlife nadir: result from four data sets. Econ J 127:126–142

18 Deaton A (2008) Income, Health, and Well-Being around the World: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. J Econ Perspect 22(2):53–72

19 Deaton A (2018) What do self-reports of wellbeing say about life-cycle theory and policy? J Public Econ 162(June):18–25

20 de Ree JJ, Alessie R (2011) Life satisfaction and age: Dealing with under-identification inage-period-cohort model. Soc Sci Med 73(1):177–182

21 Deutsch JH., Musahara, H, Silber J (2016) On the measurement of multidimensional well-being in some countries in eastern and southern Africa. In Poverty and Well-being in East Africa edited edited by Hashemati, A. Springer: 191–214

22 Diener E, Suh M (1998) Subjective well-being and age: an international analysis. Annu Rev Gerontol Geriatr 17:304–324

23 Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL (1999) Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychol Bull 125:302–376

24 Easterlin RA (2003) Explaining happiness. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100(19):11176–11183

25 Easterlin RA (2006) Life cycle happiness and its sources: intersections of psychology, economics and demography. J Econ Psychol 27(4):463–482

26 Ferrer-i-Carbonelli A, Frijters P (2004) How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? Econ J 114(497):641–659

27 Freund AM, Baltes PB (1998) Selection, optimization and compensation as strategies of life management: correlations with subjective indicators of successful aging. Psychol Aging 13:531–543

28 Frey B, Stutzer A (2002) The economics of happiness. World Econ 3(1):1–17

29 Frijters P, Beaton T (2012) The mystery of the U-shaped relationship between happiness and age. J Econ Behav Organ 82:525–542

30 Graham C, Pozuelo JR (2017) Happiness, stress, and age: how the U curve varies across people and places. J Popul Econ 30:225–264

31 Hamarat E, Thompson D, Steele D, Matheney K, Simons C (2002) Age differences in coping resources and satisfaction with life among middle-aged, young-old and oldest-old adults. J Genet Psychol 163(3):36–367

32 Hellevik O (2017) The U-shaped age-happiness relationship: real or methodological artifact? Qual Quant 51:177–197

33 Helliwell JF (2019) Measuring and using happiness to support public policies. NBER Working Paper #26529.

34 Helliwell JF, Huang H, Wang S (2019) Changing world happiness. In World Happiness Report, 2019, edited by J.F. Helliwell, R. Layard and J.D. Sachs.

35 Helson R, Lohnen EC (1998) Affective coloring of personality from young adulthood to midlife. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 24:241–252

36 Hudson NW, Lucas RE, Donellan MB (2016) Getting older, feeling less? A cross-sectional and longitudinal investigation of developmental patterns in experiential well-being. Psychol Aging 31:847–861

37 Ingelhardt R (1990) Culture shift in advanced industrial society. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

38 Jebb AT, Morrison M, Tay L, Diener E (2020) Subjective well-being around the world: trends and predictors across the life span. Psychol Sci:1–13

39 Kassenboehmer SC, Haisken-DeNew JP (2012) Heresy or enlightenment? The well-being age U-shape effect is flat. Econ Lett 117(1):235–238

40 Kroh M (2011) Documentation of sample sizes and panel attrition in the German Socio Economic Panel (SOEP) (1984 until 2010). Data Documentation 59. Berlin.

41 Lachman ME (2015) Mind the gap in the middle: a call to study midlife. Res Hum Dev 12:327–334

42 Leland J (2018) Happiness is a choice you make: lessons from a year among the oldest old. Sarah Crichton Books

43 Morgan R, O’Connor KJ (2017) Experienced life cycle satisfaction in Europe. Rev Behav Econ 4:371–396

44 Mroczek DK, Kolanz CM (1998) The effect of age on positive and negative affect: a developmental perspective on happiness. J Pers Soc Psychol 75:1333–1349

45 Mroczek DK, Spiro A (2005) Change in life satisfaction during adulthood: findings from the Veterans Affairs Normative Aging study. J Pers Soc Psychol 88:189–202

46 Myers DG (2000) The funds, friends, and faith of happy people. Am Psychoanal 55(1):56–67

47 Myers DG (1992) The pursuit of happiness. Avon Books, New York

48 Okma, P, Veenhoven R (1996) Is a longer life a better life? Happiness of the very old in 8 EU countries. Manuscript.

49 Palmore E, Luikart C (1972) Health and social factors related to life satisfaction. J Health Soc Behav 13(1):68–78

50 Piper (2015) Sliding down the U-shape? A dynamic panel investigation of the age-well-being relationship, focusing on young adults. Soc Sci Med 143:54–61

51 Pokimica J, Addai I, Takyi BK (2012) Religion and subjective well-being in Ghana. Soc Indic Res 106:61–79

52 Ranjbar S, Sperlich S (2019) A note on empirical studies of life-satisfaction: unhappy with semiparametrics? J Happ Stud, First Online16 (September 2019)

53 Rauch J (2018) The U-shape of happiness. St. Martin’s Press, New York

54 Rauch J (2019) The Happiness Curve. Why Life Gets Better After 50. Thomas Dunne Books, Macmillan

55 Schwandt H (2016) Unmet aspirations as an explanation for the age U-shape in well-being. J Econ Behav Organ 122:75–87

56 Shams K, Kadow A (2019) The relationship between subjective well-being and work–life balance among labourers in Pakistan. J Fam and Econ Issues, Springer 40(4):681–690

57 Shields MA, Price SW (2005) Exploring the economic and social determinants of psychological well-being and perceived social support in England. JRSS (Series A) 168:513–537

58 Steptoe A, Deaton A, Stone AA (2015) Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet 385:640–648

59 Stone AA, Schwartz J, Broderick J, Deaton A (2010) A snapshot of the age distribution of psychological wellbeing in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107(22)

60 Sulemana I (2015a) The effect of fear of crime and crime victimization on subjective well-being in Africa. Soc Indic Res 121(3):849–872

61 Sulemana I (2015b) An empirical investigation of the relationship between social capital and subjective well-being in Ghana. J Happiness Stud 16(5):1299–1321

62 Sulemana I, Doabil L, Anarfo EB (2019) International remittances and subjective wellbeing in Sub-Saharan Africa: a micro-level study. J Fam Econ Iss 40(3):524–539

63 Sulemana I, Iddrisu AM, Kyoore JE (2017) A micro-level study of the relationship between experienced corruption and subjective wellbeing in Africa. J Dev Stud 53(1):138–155

64 Ulloa BFL, Moller V, Sousa-Poza A (2013) How does subjective well-being evolve with age? A literature review. J Popn Ageing 6:227–246

65 Van Landeghem B (2012) A test for the convexity of human well-being over the life cycle: longitudinal evidence from a 20-year panel. J Econ Behav Organ 81(2):571–582

66 Weiss A, King JE, Inoue-Murayama M, Matsuzawa T, Oswald AJ (2012) Evidence for a midlife crisis in great apes consistent with the U-shape in human well-being. PNAS, 4 109(49):19949–19952

67 Whitbourne SK (2018) That midlife happiness curve? It’s more like a line. Psych Tod. In: September 18th

68 Wunder C, Wiencierz A, Schwarze J, Küchenhoff H (2013) Well-being over the life span: Semi-parametric evidence from British and German longitudinal data. R E Stat 95:154–16

69 Bell DNF, Blanchflower DG (2019) The well-being of the overemployed and the underemployed and the rise in depression in the UK. J Econ Behav Organ 161:180–196

70 Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ (2008b) Hypertension and happiness across nations. J Hlth Econ 27(2):218–233

71 Bleischmann G (2014) Heterogeneity in the relationship between happiness and age: evidence from the German Socio-Economic Panel. Ger Econ Rev 15(3):393–410

72 Clark AE (2019) Born to be mild? Cohort effects don’t (fully) explain why well-being is U-shaped in Age. In: Rojas M (ed) The Economics of Happiness. How the Easterlin Paradox Transformed Our Understanding of Well-Being and Progress, 2019, Springer, pp 387–408

73 Glenn N (2009) Is the apparent U-shape of well-being over the life course a result of inappropriate use of control variables? A commentary on Blanchflower and Oswald (66:8, 2008, 1733–1749). Soc Sci Med 69(4):481–485

74 Carstensen LL, Turan B, Scheibe S, Ram R, Ersnser-Hershfield H, Samanez-Larkin GR, Brooks KP, Nesselroade JR (2011) Emotional experience improves with age: evidence based on over 10 years of experience sampling. Psychol Aging 26:21–33